The Prodigy spent much of 19 touring around the world, and made a splashy appearance at the 1995 Glastonbury Festival, proving that electronica could make it in a live venue.

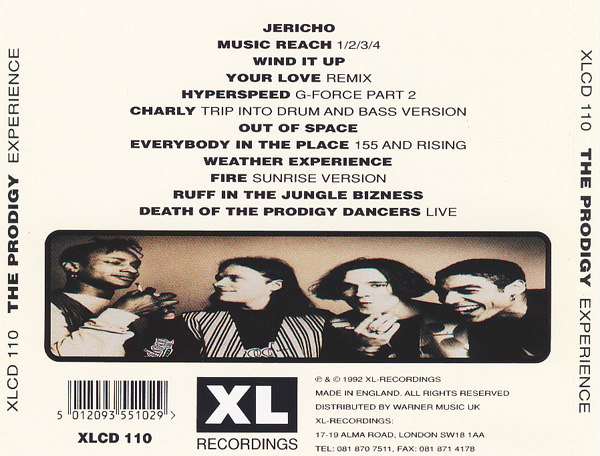

The album was also nominated for a Mercury Music Prize as one of the best albums of the year. Music for the Jilted Generation entered the British charts at number one and went gold in its first week of release. Late 1993 brought the commercial release of "Earthbound" (as the group's seventh consecutive Top 20 singles entry, "One Love").Īfter several months of working on tracks, Howlett issued the next Prodigy single, "No Good (Start the Dance)." Despite the fact that the single's hook was a sped-up diva-vocal tag (an early rave staple), the following album, Music for the Jilted Generation, provided a transition for the group, from piano pieces and rave-signal tracks to more guitar-integrated singles like "Voodoo People." The album also continued the Prodigy's allegiance to breakbeat drum'n'bass though the style had only recently become commercially viable (after a long gestation period in the dance underground), Howlett had been incorporating it from the beginning of his career. He also released the white-label single "Earthbound" to fool image-conscious DJs who had written off the Prodigy as hopelessly commercial. During 1993, Howlett added a ragga/hip-hop MC named Maxim Reality (Keeti Palmer) and occupied himself with remix work for Front 242, Jesus Jones, and Art of Noise. Mixing chunky breakbeats with vocal samples from dub legend Lee "Scratch" Perry and the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, it hit the Top Ten and easily went gold. The Prodigy showed they were no one-anthem wonders in late 1992 with the release of The Prodigy Experience, one of the first LPs by a rave act. (It wasn't long before a copycat craze saw the launch of rave takeoffs on Speed Racer, The Magic Roundabout, and Sesame Street.) Two additional Prodigy singles, "Everybody in the Place" and "Fire/Jericho," charted in the U.K. It hit number one on the British dance charts, then crossed over to the pop charts, stalling only at number three. Six months later, Howlett issued his second single, "Charly," built around a sample from a children's public service announcement. Howlett's recordings gained the trio a contract with XL Records, which re-released What Evil Lurks in February 1991. After Howlett met up with Keith Flint and Leeroy Thornhill (both Essex natives as well), the trio formed the Prodigy later that year.

His first release, the EP What Evil Lurks, became a major mover on the fledgling British rave scene in 1990. The fledgling hardcore breakbeat sound was perfect for an old hip-hop fan fluent in uptempo dance music, and Howlett began producing tracks in his bedroom studio during 1988. He began listening to hip-hop in the mid-'80s and later DJed with the British rap act Cut to Kill before moving on to acid house later in the decade. Howlett, the prodigy behind the group's name, was trained on the piano while growing up in Braintree, Essex. Even before the band took their place as the premiere dance act for the alternative masses, the Prodigy had proved a consistent entry in the British charts, with over a dozen consecutive singles in the Top 20. Yet it was always producer Liam Howlett's studio wizardry that launched the Prodigy to the top of the charts during the late-'90s electronica boom, spinning a web of hard-hitting breakbeat techno with king-sized hooks and unmissable samples.ĭespite electronic music's diversity and quick progression during the '90s - from rave/hardcore to ambient/downtempo and back again, thanks to the breakbeat/drum'n'bass movement - Howlett modified the Prodigy's sound only sparingly swapping the rave-whistle effects and ragga samples for metal chords and chanted vocals proved the only major difference in the band's evolution from their debut to their worldwide breakthrough with third album The Fat of the Land in 1997. Ably defeating the image-unconscious attitude of most electronic artists in favor of a focus on frontmen Keith Flint and Maxim Reality, the group crossed over to the mainstream of pop music with an incendiary live experience that approximated the original atmosphere of the British rave scene, even while leaning close to arena rock showmanship and punk theatrics. The Prodigy navigated the high wire, balancing artistic merit and mainstream visibility with more flair than any electronica act of the 1990s.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)